Introduction

Problem statements aren’t a new concept.

Charles Kettering once said, “A problem well stated is a problem half solved.” It’s a quote that quality professionals know instinctively, even if they don’t know its origin. Einstein’s version is a bit more dramatic: “If I had an hour to solve a problem, I’d spend 55 minutes thinking about the problem and five minutes thinking about solutions.”

Both remind us of the same truth: when it comes to complex systems – especially laboratories – it’s not the quick fix that saves us. It’s the clarity with which we define the issue.

Why a Strong Problem Statement Matters

In laboratory environments, we often face persistent issues—flawed processes, human errors, recurring non-conformances. And when things go wrong, we’re tempted to dive straight into fixes. This is intuitive.

Fix the problem and move on. We have work to do!

But treating symptoms without understanding the big picture leads to messy outcomes. Such as, repeat failures, and system breakdowns.

There is no requirement for a formal problem statement in ISO/IEC 17025:2017. Problem statements are a tool in your toolbox.

It’s a bridge:

- Between chaos and clarity

- Between symptoms and root causes

- Between reactive fixes and proactive planning

The time we spend understanding the problem helps us communicate it clearly. That means we have a better chance of finding the real cause. That’s going to save us from having to solve the same problem over and over again.

Defining "Problems" in Our World

In quality management, “problem” isn’t a dirty word. , its our reality. We see them every day. Anything that blocks progress, threatens reliability, or threatens compliance qualifies. We know from entropy that all systems naturally drift toward chaos unless we apply energy to manage and maintain it

Think of it like constantly sweeping sand back in the sandbox. It’s not glamorous, but it’s essential.

Sometimes, problems are routine. Other times, they’re organizational earthquakes requiring stakeholder alignment, resource commitments, and reputation management. It’s not always super clear. The difference lies in how clearly the problem is defined.

When Should We Use a Problem Statement?

Not every problem is going to require a formal problem statement.

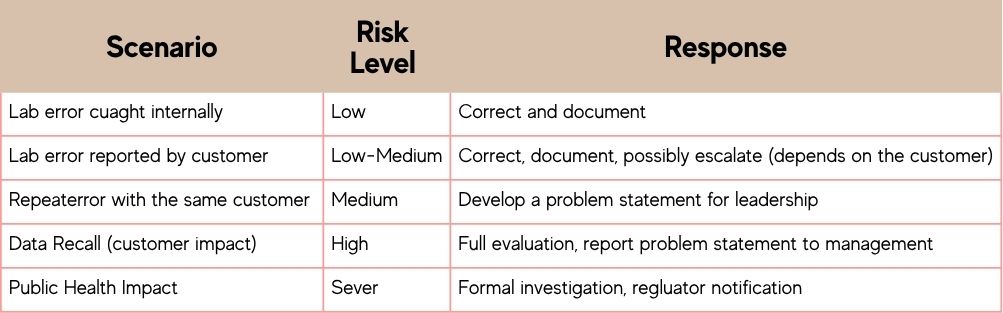

Our goal is to frame the problem in terms of severity and impact.

Initially, most problems require a risk assessment. That is to say, a quick problem triage rather than a full FMEA risk analysis.

Here’s a quick snapshot of what I mean:

If your problem could become a big deal, and you find yourself needing to investigate and correct the causes, the more you’re going to want to develop a problem statement. When you do that, you’ll be able to keep your response focused and effective

Final Thought: Fixing Without Framing Is a Trap

A band-aid fix may look tidy, but that’s deceptive. After all, the band-aid is pretty cosmetic. Especially if you don’t know what’s causing the bleed.

When you rush to correct a symptom without pausing to understand the problem, you’re not actually correcting it. And in a lab, that can mean wasted time, misallocated resources, or worse—damaged customer trust.

So next time something goes wrong, don’t just ask how to fix it. Ask what exactly is broken—and why. That’s the thinking that leads to truly transformative outcomes.

Next in the series: Many labs struggle to clearly define nonconforming work, leading to misdirected corrective actions and system fatigue. In Part Two, we explore why this problem persists—and how applying triage principles can clarify scope, support quality teams, and protect valuable resources.