Recap of Posts 1 and 2

Post 1: A Problem Well Stated—The Bridge to Better Outcomes

- Explored the importance of defining problems as the smartest first move.

- Discussed the psychology and philosophy behind the problem-first approach.

- Introduced problem statements as strategic tools.

Post 2: Why We Fail at Defining Problems

- Highlighted common pitfalls in crafting problem statements.

- Discussed the impact of weak problem statements on outcomes.

- Shared the Gumball Theft analogy to illustrate overdoing investigations.

Introduction

- Who: Technician on prep duty

- What: Reagent failed spec due to unexpected concentration

- When: Occurred during Monday prep batch

- Where: Workstation B, known for variable lighting

- Why: Preliminary review suggests visual measurements instead of pipetting

- How: Solution added manually, bypassing calibrated equipment

- How Much: Concentration off by 22%, prompting retests

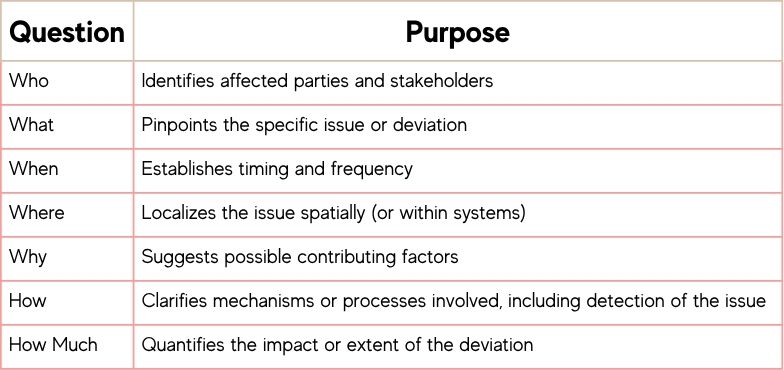

The 7-Question Matrix

This is certainly not a new concept. We all learned about the 5-W’s in grade school English lessons. It turns out that storytelling is powerful in problem solving. Check out this article for an even deeper dive.

Problem Statement or Root Cause Analysis—Which Comes First?

- Begin with metadata thinking: What do we know right now?

- Let the problem statement evolve as you gather insights.

- Then, when the picture is clearer, move into root cause thinking with confidence.

Metadata vs. Root Cause Thinking

What's the difference?

At this point, it’s crucial to talk about the difference between metadata and root cause thinking.

- Metadata Thinking captures surface-level signals—error codes, logs, user reports. It tells you what is happening and where.

- Root Cause Thinking digs deeper to uncover why the problem exists and how to prevent it.

Why it matters:

Metadata helps triage and categorize issues quickly, but root cause thinking drives resolution and systemic improvement. Strong problem statements bridge both—using metadata for clarity and root cause thinking for depth.

Metadata thinking leads connects data with an anecdotal description of the problem.

By combining clarity, context, impact, and root cause orientation, your problem statements become powerful tools for triage, collaboration, and resolution.

Case Study - The Dilution Error

- Who: Technician on prep duty

- What: Reagent failed spec due to unexpected concentration

- When: Occurred during Monday prep batch

- Where: Workstation B, known for variable lighting

- Why: Preliminary review suggests visual measurements instead of pipetting

- How: Solution added manually, bypassing calibrated equipment

- How Much: Concentration off by 22%, prompting retests

Be Hard on the Process, Not the Person

To help teams quickly capture metadata during triage and build stronger problem statements, we’ve created a downloadable 7-Questions Matrix Worksheet. This visual tool guides users through the key elements of effective problem framing—bridging metadata signals with root cause thinking.

Use it during triage sessions to:

– Organize contextual signals (metadata)

– Prompt deeper inquiry into underlying causes

– Align teams around actionable problem statements